use arrow keys on keyboard or click on image to advance

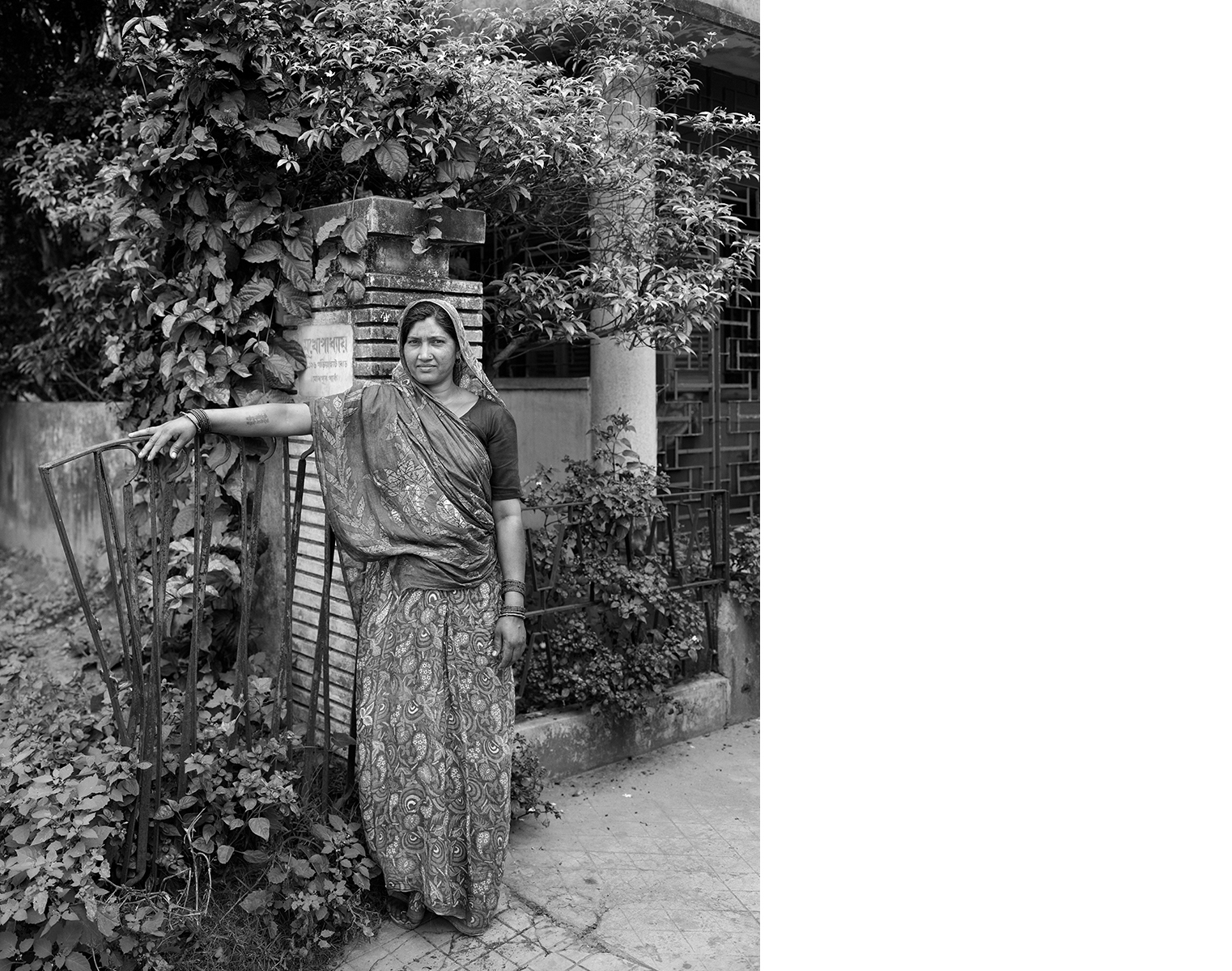

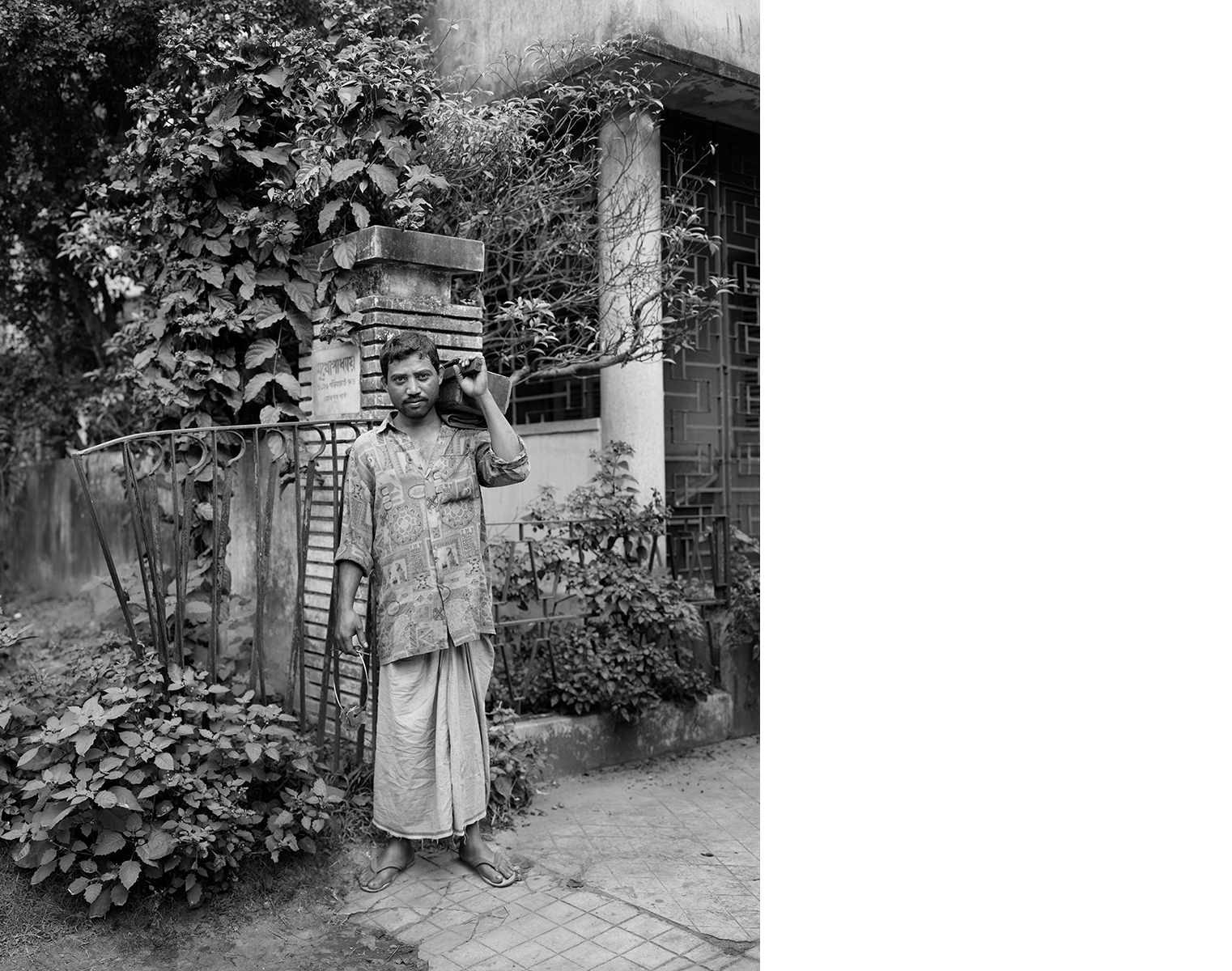

The hawkers of Kolkata pass the house most any time as long as there is daylight. We hear them before we catch sight of them, their instruments and cries in melody with the horns and bicycle bells, the calls of crows and barking dogs that make the sound in every avenue and byway of this symphonic metropolis. Mr. Ghosh, our elderly landlord, dressed in a sleeveless white shirt and dhoti, rests on his second-story balcony under a ceiling fan. His view leads directly down the driveway to the street and from his perch, he is sovereign: he has only to lift his hand and passersby will diverge from the procession, come to do his bidding.

Mostly, Mr. Ghosh reads and is indifferent to the street. Only occasionally does he beckon the rag picker who will rid the household of accumulating papers, bottles, or bits of fabric in exchange for a few paisa. Or he may call the vendor of crabs who supplies, with great lassitude, provisions for the cook. Perhaps he waves to the ice cream man an unspoken request for a popsicle for his seven-year-old granddaughter or to the man with coconuts and a scythe, refreshment please. Sometimes his wife stands beside him, pale in her cotton sari and silver hair. Sometimes the little girl, deep brown eyes, lustrous dark bob, stands there too.

We arrive in that driveway in the dead of night. It is cold in Kolkata, a seeping, blood thinning cold, colder than the east coast we have left behind in mid-winter for this other sub-tropical east coast. The fog in the air is the smoke of thousands of open coal fires held there by the dark physics of thermal inversion. City of fifteen million souls, spectral without sun, men emerging from the fog in pale shawls, lost again beyond the gleam of intermittently illuminated headlights. There are no hawkers now. Exchange takes its rest.

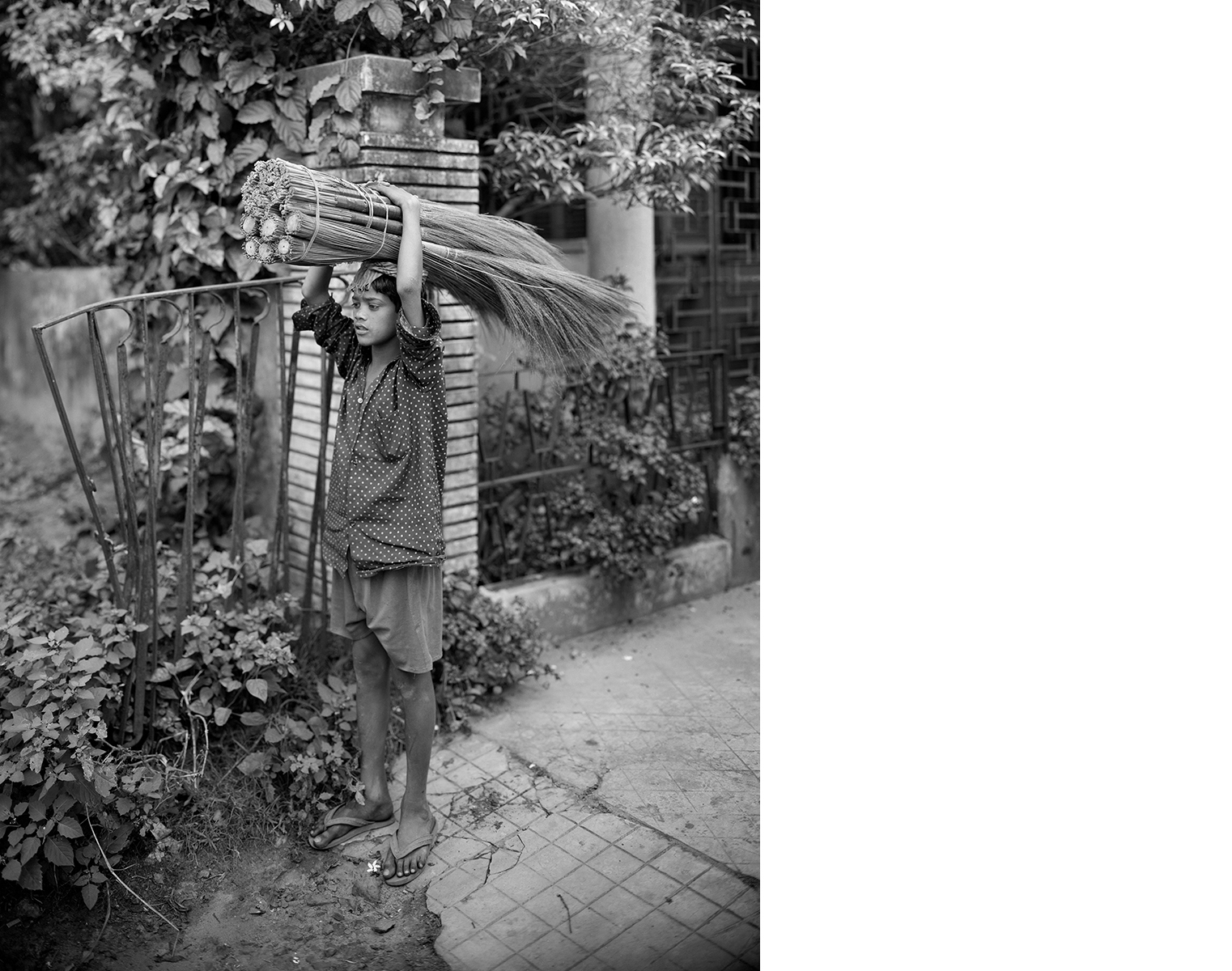

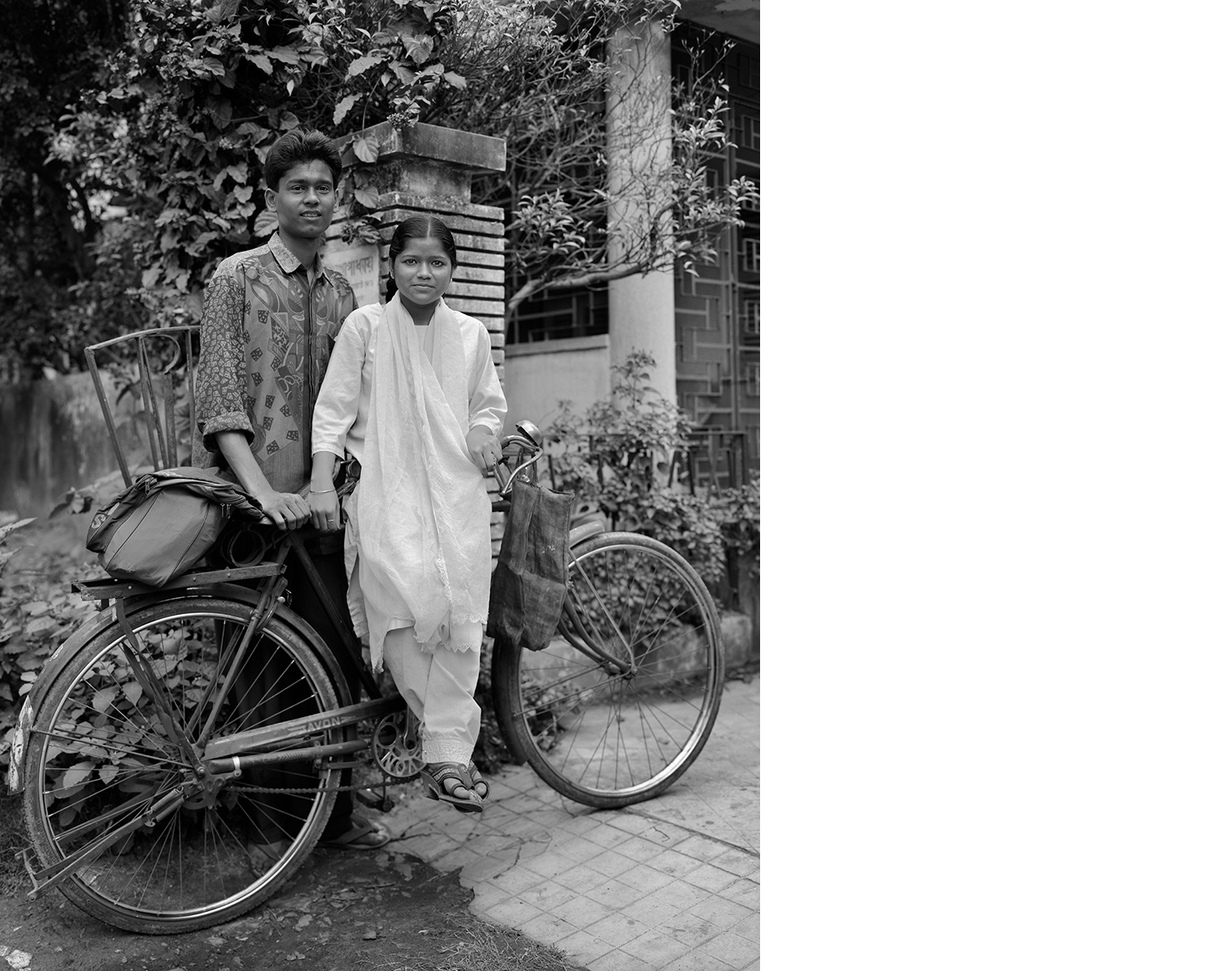

In the filtered light of morning, the schoolgirls and their ayah pass, a young couple bicycles to the university; she rides the handlebars. Later, as the sun sends waves of warmth to our little street, visitors come to the house. Domestic servants make their rounds. Water is delivered to our immediate neighbor. Kolkata does not yet have malls and supermarkets. We buy from peddlers at street markets, from wandering hawkers. We cook meals and boil water for ourselves and milk for our child on a two-burner stove attached to a propane tank shaped like Little Boy which stands ominously under our counter. We learn to watch patiently and in wonder as the pageant passes the end of our driveway: teachers and transvestites, worshippers and the worried, the circus performer cuddling his monkeys.

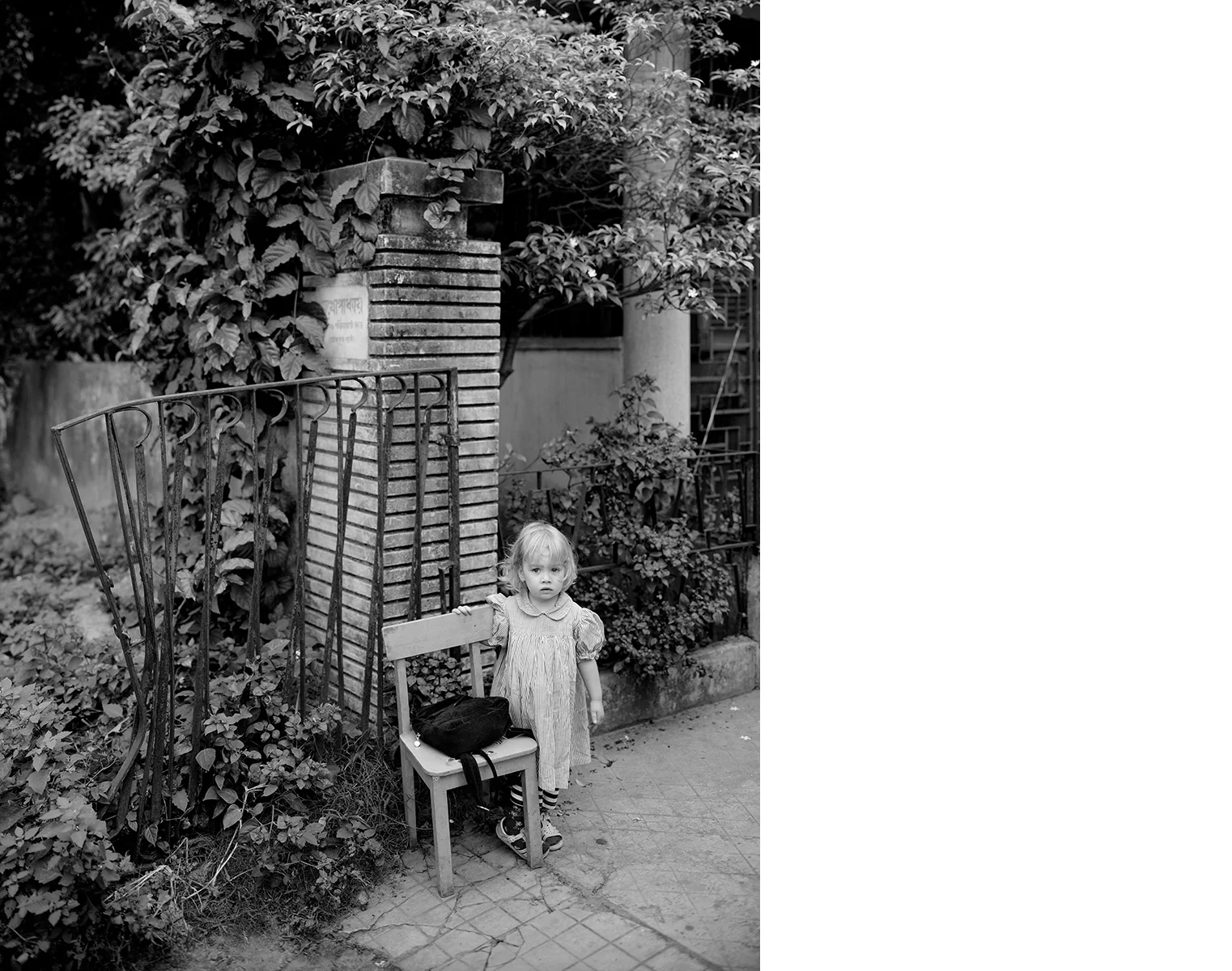

Our daughter is tow-headed and two. In the streets people pinch her cheeks and touch her hair, sometimes inquiring why her hair is old before she is. We buy an edition of Mother Goose in the bookstall at Newmarket and read about hot cross buns, black hens and sheep. Living here entails travel across time and space into the deeply unfamiliar, but we find clues to this version of existence through the eyes of our daughter, through the rhymes we read to her. Soon we find a post at the bottom of the driveway, my mahogany camera affixed to its metal tripod. In Bengali, we learn to say, “May I take your photograph?”

Brookline

September 2010